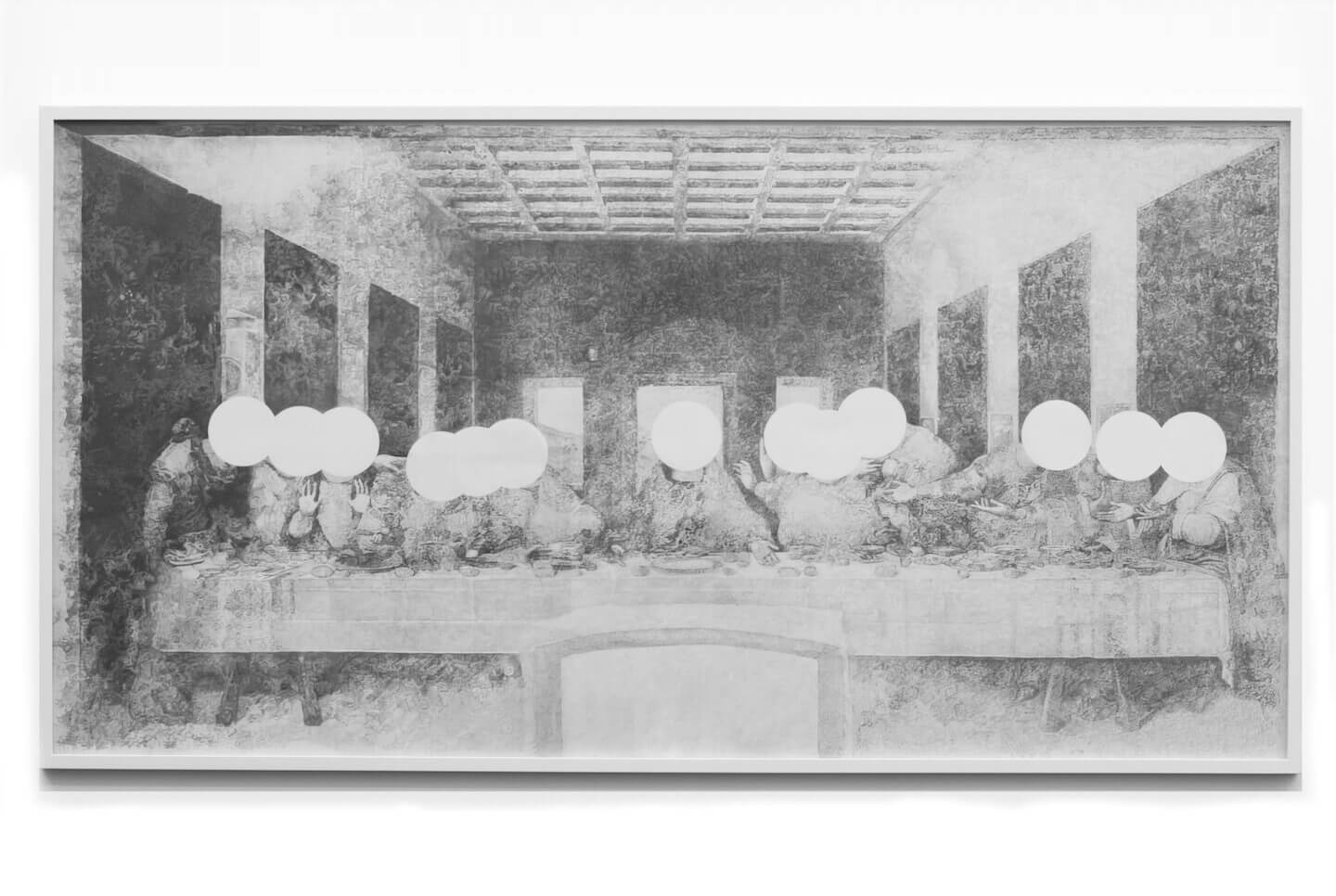

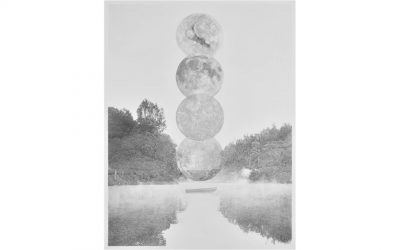

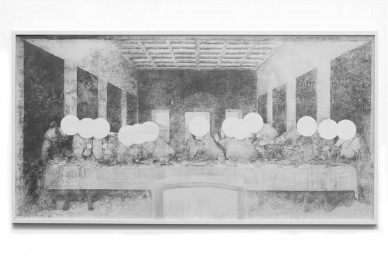

paper 224 g/m2

White wooden frame, Plexiglass

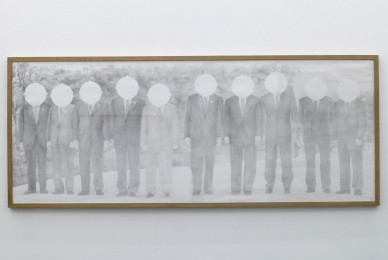

53 7/8 x 104 3/4 in.

56 1/4 x 107 1/8 in. framed

papier Canson 224 g/m2

Encadrement bois blanc, Plexiglas

137 x 266 cm

143 x 272 cm encadré

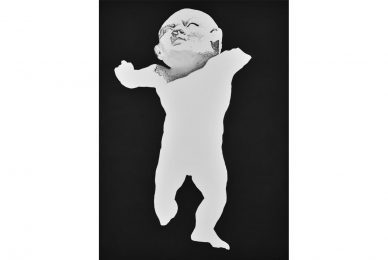

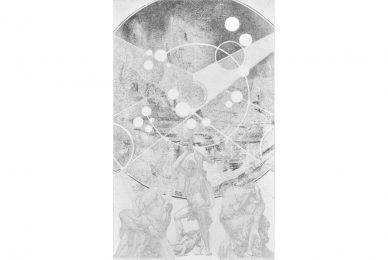

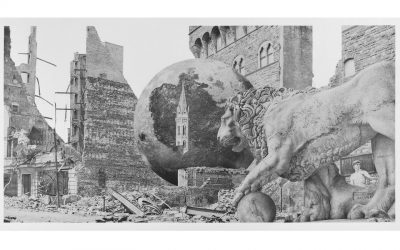

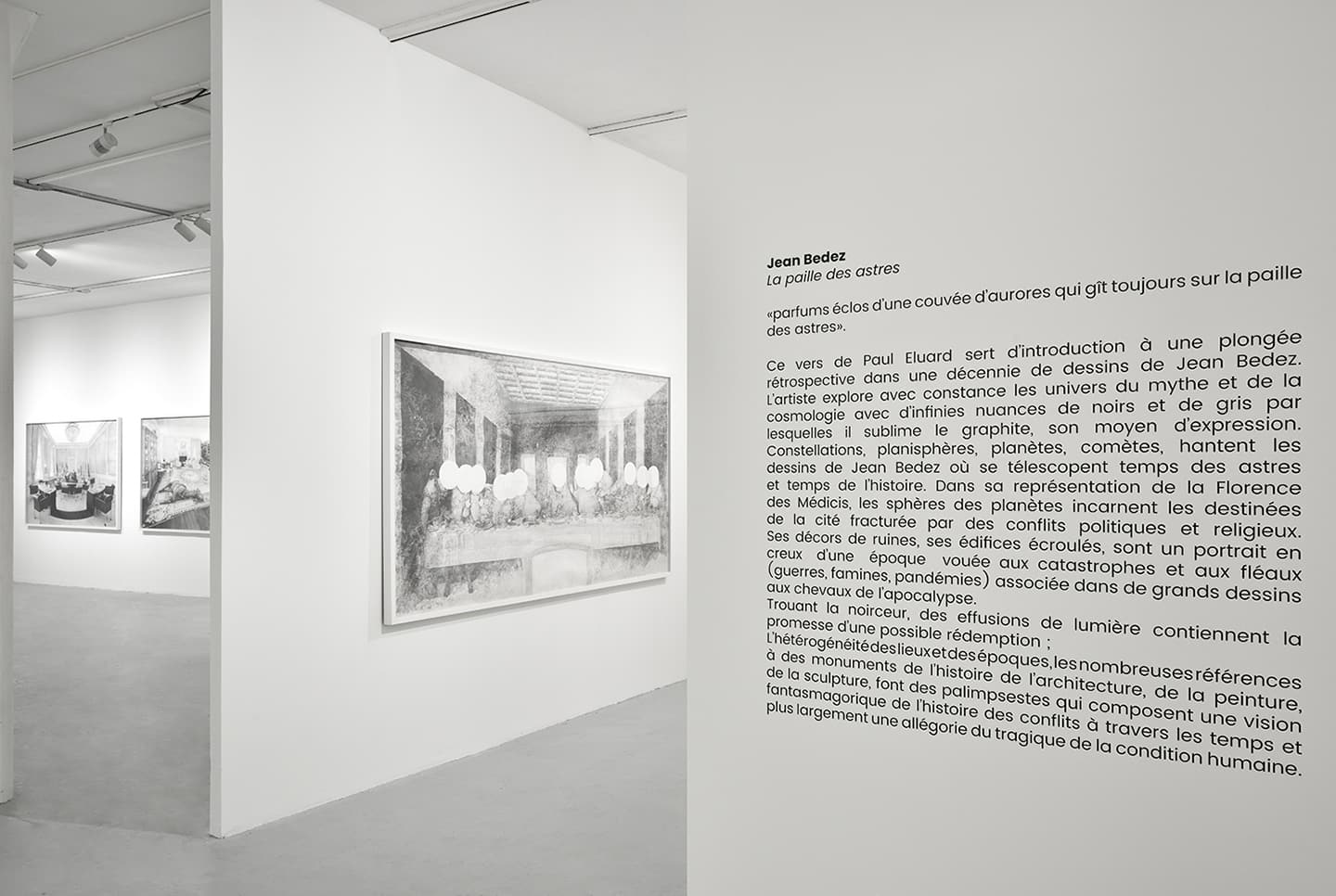

Le Cénacle

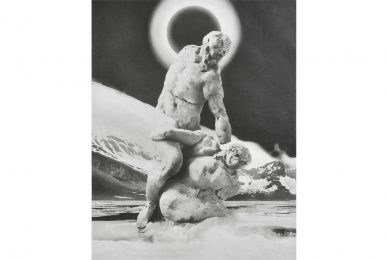

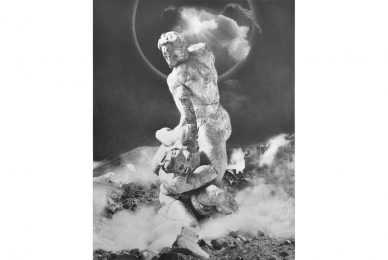

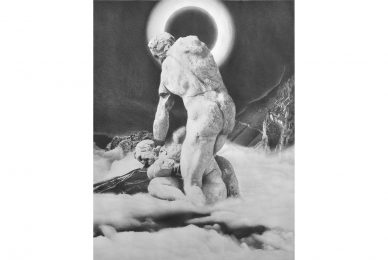

In Le Cénacle Jean Bedez revisits a monument of art history, a genuine turning point in the history of religious iconography: The Last Supper. Reflecting the humanist values of the day, the human figure is, implicitly, the central subject of this painting. This is reflected in the great detail and care in Leonardo da Vinci’s portrayal of Christ and the apostle’s expressions – showing the “movements of their soul.” In Bedez’s version, these disappear behind a white halo.

But we find the same carefully rendered perspective, and even a kind of radiographic treatment of the original, recreating the sfumato of the original through successive layers of graphite. But just as he recreates details lost to successive restorations and the effects of time, Bedez also blurs the image, pushing the sfumato technique to extremes and erasing the faces, making is impossible to focus on the human face.

The artist thus calls into question the centrality of man on which the humanist vision was based, and also the political dimension of this kind of representation: the crests of the patrons have also disappeared from his drawing.